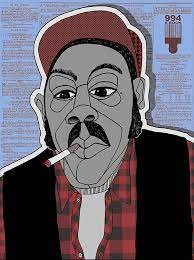

Here is my piece from the recent published anthology by Ajuan Mance entitled “1001 Black Men: Portraits of Masculinity at the Intersection.”

https://stackeddeckpress.com/product/1001-black-men-portraits-of-masculinity-at-the-intersections/

Joe Camel was everywhere when I was a child. He was on television, he was on bus stop benches, and he was selling cigarettes on billboards in the same manner that Billy Dee Williams was hawking Colt 45. This was the late 1980s which represented the last days that such blatant targeted advertisements would be allowed in the African-American community. My childhood was impacted by Joe Camel in the same way that kids of today are being impacted by Blueberry vape pens. The drawing of Joe Camel smoking a cigarette as he played a game of pool was hella fly to me. In my young preadolescent opinion, even though he didn’t speak, he was the dopest cartoon image ever. He had more charisma than Bugs Bunny and was a bigger boss than Leonardo from the Ninja turtles. Even more significant than that was the fact that he was the mascot for my Uncle Red’s preferred brand of smokes. Which meant that he was present at my grandmother’s house, family get togethers, or where ever my uncle happened to be.

When I was little I thought my Uncle Red was the coolest man in the world. Partly because he had been to prison and partly because he used to be a pimp, but really because he smoked Camel cigarettes. He would blow smoke rings in the backroom of my grandmother’s house and let the kids break them up with our fingers. He had a thousand stories and never told the same one twice. In retrospect all of them were wildly inappropriate for a boy in elementary school to hear, but I still soaked up all of his game like a sponge. Anytime I was able to walk with him down 3rd Street in the Bayview section of San Francisco or down E14th in East Oakland it was like basking in the light of a celebrity.

Uncle Red is sure to walk on the outside of me and my cousins so that he is the one closest to the traffic. He lets us run to the corner while he stays behind with a Camel cigarette pursed in between his lips. We make it to the corner and stop to wait for him before we cross the street. I turn around totally out of breath and look back at my uncle who is taking out his lighter to light up another cigarette. He is wearing white leather platform shoes, white bell bottoms, a white button up shirt, a white blazer, and a nappy chest. His hair is combed back. His hairline is barely receding. The sun catches his bronze complected face in a way that makes him look like a mixture of Goldy from The Mack and Joe Camel himself. By the time he catches up with us we have caught our breath. We walk together across the street and into the liquor store where I get animal crackers and a soda. My cousins get Lemonheads, Jolly Ranchers, and Funyuns. My uncle asks for Camel Menthols which are behind the counter. Uncle Red pays for everything. While he steps out of the door he flicks his cigarette butt onto the concrete and I run to step on it first. He opens up the new box of Camel Menthols and shakes another cigarette into his palm, then he places it into his mouth. My cousins and I run ahead to the next corner and I am in the lead.

My uncle went to prison fairly often for drug related offenses. When he was granted parole he went straight from San Quentin to my grandmother’s house where his shoe collection was there waiting for his release. He had snake skin boots, gator skin shoes, suede platforms, and loafers of every imaginable color. Most of them were still in their boxes in my grandmother’s backroom. The backroom at my grandmother’s house was central to family life because that was where the television was located. There was another television in the living room, but we couldn’t watch that one. The living room was just for show. It had plastic seat covers on all of the furniture and if it wasn’t a very special occasion my grandmother would slap you for setting your foot in there. So we would watch tv with my Uncle Red in “his room.”

On this particular day he is fidgety and slightly annoyed. He taps his box of Camels but it is empty. He then takes a deep breath, curses, and asks my sister to go to the corner store and buy him some smokes. My sister is 12-years-old. I am 8. He gives us enough money to buy some candy with the change and we’re off. We walk down Shafter Avenue to get to 3rd Street where the Arab store is. We bring our candy to the register. My sister asks for a pack of Camel menthols. The Arab man behind the counter tells her that she is too young. She replies that they’re not for her. They’re for her uncle. The Arab man says that she needs a note. We go back to my grandmother’s house and tell Uncle Red. He says to my sister “Well write a note.” My sister writes a note in her very best cursive handwriting and signs my uncle’s name on the bottom of it. We go back to the corner store and purchase the cigarettes without a problem.

Over the next few decades there would be a justifiable war on cigarettes and the harm that they had done to generations of people. They would be exposed for lying about all of the health risks that their products cause and for specifically marketing menthols—which is the most addictive form of cigarette—to the African-American community. Billboards and commercials promoting tobacco products would be strictly prohibited. Joe Camel became a relic and places of business that sold cigarettes to minors would face serious sanctions. My grandmother passed away in 2016 and the family lost her home in the Bayview. My uncle, however, is still going.

About a year ago I saw him on Macarthur Boulevard in Oakland. He had checked himself into a program for drug addiction. The program was run through a church. I passed the church and saw him standing out front. He had finally given up the bell bottoms and the platforms for blue jeans and sneakers. Yet he still was wearing a button up shirt and had a nappy chest. I pulled over and called him to my car. I got out and hugged him in the street. He said he was proud of me and he meant it. I told him that I was proud of him too and I thanked him for always making me feel safe as a child. We reminisced for a minute and laughed, but he looked incomplete. When I was about to get in my car to leave he stopped me.

“Say nephew. Do you have some change? I need some smokes.”

“For sure,” I said with no hesitation.

I gave him a bill and then gave him another hug. As I drove off I saw him walking toward the corner store in my rearview mirror. I sped through the green light at the corner.

-Roger Porter